Wrangling the Beast: Playing with Structure in the First Novel

Moderator: Joy Baglio; Panelists: Emma Komlos Hrobsky, Raluca Albu, Swati Khurana

Writers are often trying to subdue this beast of structuring something so large as a novel. The five panelists at this virtual panel at this year’s AWP conference gave their best advice on structure, and provided suggested reading and other tools to help you through.

It’s hard to think of structure as separate from story—like living in a house without the actual frame of the house.

Joy: The way I think of structure has a lot to do with story and plot, but also how it unfolds. It’s hard to think of structure as separate from story—like living in a house without the actual frame of the house. We can experience everything about the inside of the house—the furniture, decorations, what’s on the floors—but we’re also always experiencing the actual shape of the rooms, the walls, the full structure of the house.

Please describe what you’re working on and how you arrived at your novel’s structure.

Emma: I’ve been working on a novel for the last three-and-a-half years set in the world of experimental physicists. I had a clear picture about what I wanted the book to convey about motherhood, family, and particle physics, but less of a clear sense of structure. I have hard time making myself sit down and write because I work as an editor and I’m reading and working with writing all day. So I gave myself permission to write any part of the book I wanted—whichever part was most important to me at the time—and I ended up with fragments. It got the work done, but it was horrible for structure. I ended up playing with different structures until I arrived at a more straightforward, linear structure than I had thought it would be.

Raluca: I agree that giving yourself room to play helps you break away from expectations and tricks the mind into doing something different. My novel is about a secret police file of an illegal abortion doctor in communist Romania. It began as an immigrant story about my family. I based the policeman on my father, but the mother character was vague. So I wrote her through first-person. And this sneaky, smart voice came out that sounded like she was talking to someone. One thing led to another and I realized she was talking to an interrogator. After that I was able to nail that structure down and disengage so that suddenly everything was a surprise and became a little more fun to write.

Swati: My novel started in earnest seven years ago. It was set in Lahore, India from 1945-47. That’s where all of my grandparents are from and where they all migrated from. It’s a religiously plural region. I grappled with the question of how do I give a female character more agency, knowing the constrictions that existed for my grandmother. I imagined her as an artist and how, in a patriarchal world, women able to seize power did so through a male accomplice, which was her father. I started a prologue from a granddaughter but didn’t know what it was, so I removed it. When I had like 60,000 words and it still wasn’t making sense, I realized that narrator I got rid of is the person telling the story of her grandparents. So over the past three years it’s taken a different form. I decided to write it as a fictional podcast that sounds like a true crime podcast. So it has that level of discovery. Following conventions of dramatic writing, like TV pilots, gave me so much more to play with than just a novel.

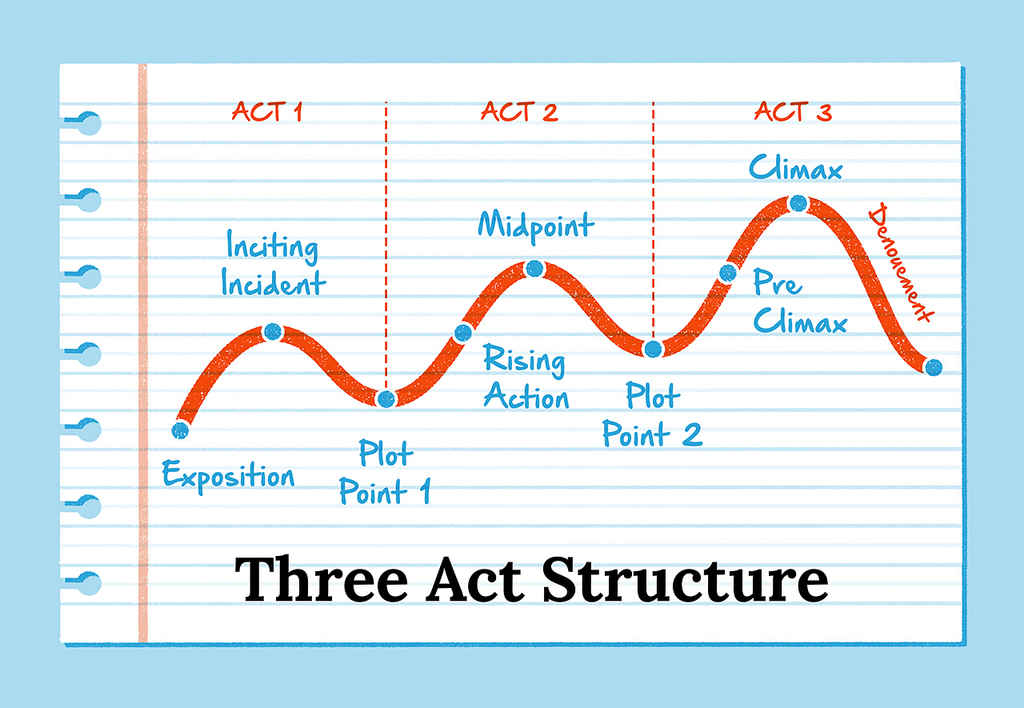

Joy: I love the idea of following sparks of what is fun and what interests us most. I started with a short story that I wanted to adapt to a novel about two sisters dealing with the fallout after their mermaid mother returns to ocean, and navigating their half-mermaid identity. As I pushed it forward into their lives, it wasn’t flowing and I was stuck. So I tabled it for over a year. When I came back to it, I had a breakthrough thought that it wants to live most in these fragment moments, these vignettes. So I reconceived of the structure, and it took off so much pressure of what I felt wasn’t working. My other novel is a ghost story about a protagonist who inherits a house full of ghosts that are searching for something that relates to her in her failed marriage. I used a traditional three-act structure for this one, which helped me. Something about this one works in that more traditional way.

What’s the biggest hurdle you’ve come up against in your work and what shifted you out of it?

Raluca: Mine was how do I make it realistic, to sound like a real police file and fill in information for the reader that wouldn’t necessarily show up in that file. So I read about what these files are like. A woman who did this actual work said they read like novels and the files sometimes include postcards and letters. I didn’t want to make readers do so much work at connecting the dots, so I decided to lean into it and not make it so much of a realistic file. It should be a more engaging story instead of letting the form stop it from happening.

Swati: I felt so much pressure because of these perfect novels that existed about the Indian partition. Finding this form and discovering this idea that I could maybe write this as fake nonfiction, in auditory form, made the hurdle of the grand failure to write a novel about partition turn into an experiment of how can I write a literary novel rooted in realism for an audio-fictional landscape?

So many of the hurdles get jumped with playfulness and experimentation.

Emma: Again, so many of the hurdles get jumped with playfulness and experimentation. I decided to have a mother and daughter each take half the narrative. But I found that the stakes were so much higher for the mom character that it made sense for the daughter’s narrative to sort of fall away, and it released me from a structure that was boxing me in. The book got a lot wilder when I did that and brought me closer to the most emotional material. I’ve made more space for her life and her ideas by releasing some of my control over the structure.

Does your sense of story reveal the structure—structural form vs. actual content of the story?

Swati: It seems like all of us kind of decided to commit more to a character or narrator. I spent about two to three years researching and mapping my favorite contemporary novels with omniscient narrators. But when I tried to do this, that’s when I realized the person I erased was actually the narrator. In terms of the form, the title of my book changed to My Grandmother Spoke to Tigers. With podcasts, there’s incredible writing happening for the ear. You hear someone’s voice for six to ten hours, like the length of a novel, and I’m absorbing this and thinking what would my character say? What would her voice sound like?

What’s influenced how you think of structure in your writing—authors, other works, symbols, visuals, structural models? What shape is your novel?

Emma: The biggest revelation I’ve had as a writer was the realization that form was another way to iterate content and to express what the heart of the book is. That’s not incidental, it’s a way to say what you want to say. I’ve used particle physics as a sort of metaphor for family and how elements stay together and break apart. There’s lots of fun language that physics lends itself to for structure.

Joy: Form is another way to iterate content. That’s pretty much the whole topic of this panel. It’s like solving a puzzle and when it comes together it’s a fabulous experience.

Swati: I looked at a book about writing by Mary Caroll Moore—Your Book Starts Here. She actually has a five-act structure: the triggering event, the first turning point, the conflict dilemma, the second turning point, and the resolution. She noted how, in films, things get really bad about 20 minutes before the end of the film: the house has burnt down, the child has run away, the marriage is cancelled, the car has blown up. That helped me think of how I can use that for either the arc of the entire project or the arc for certain characters. Shonda Rhimes has an amazing master class called “Writing for Television” that talks about coming up with characters. That helped me really think about things where I got away from the whole MFA idea of “this is all mysterious.” Actually, this is just okay. So you want to sell a TV show, here’s what you do.

What strategies have you tried and what tools do you recommend for structure?

Raluca: The book Meander, Spiral, Explode was really helpful because I was coming at this from a screenplay approach and it was making the writing very flat. Being able to write into surprise, noticing repetitions and recursions and letting them stay there, gives a deepening as you go. If you’re planning too much it’s harder to see what’s in the margins.

Emma: (Points to a wall of papers tacked up beside her desk.) My wall is my draft of my book. It’s probably the biggest single thing I’ve done to help myself craft this. Because I had all these fragments, I realized I needed a way to see them all together. I printed them all out and went to my friend’s house with big floors and I laid them out. It was the best moment. When I could see all these pieces together, I could see concretely that I’d written a lot that did add up to narrative. I could see scenes and forward motion and see the holes. I stacked the papers very carefully, then came home and taped them together up on my wall. I call it my “mind of the killer” wall. It’s a nice, tangible reminder of my progress and it feels so good to add to it as I go.

It was the best moment. When I could see all these pieces together, I could see concretely that I’d written a lot that did add up to narrative. I could see scenes and forward motion and see the holes.

Raluca: A professor had us read a short scene we’d written and then we had someone else act it out as improv. It was awesome. The book The Situation and the Story is about how to craft strong first-person narrators in nonfiction. That gave me a lot of ideas about what’s the difference between someone’s story and the actual situation they’re in? Take Gone Girl. The first part you’re with that person and getting the information you think you need and then in part two you realize that’s not the actual whole story. So watch lots of Netflix! It’s all research.

Joy: The way the three-act structure helped me is that I tried to abandon all the terminology behind it—plot point, pitch points, etc.—and came up with an exercise called story sketching. You free-write a page or so about everything you know about your book. Don’t worry too much about how it comes out. Then look in that free-write for three natural sections and write out separate paragraphs for each of those parts. Those are your three acts. Take paragraphs and condense them down to sentences that tell you the hearts of the three different acts. This allowed me to conceive of the whole book in one thought more or less. It allowed me to identify the heart of each act and the movement between them. I then did bullet lists of what happens in each part. I change it as I go to keep it current as things change. When the writing stalls, there’s something nice about having this other way to work on it. Let me go into this planner’s studio and mess around with plot and scene ideas to get me unstuck.

Raluca: I took a sense writing workshop. Where you go inside the body of a character, explain what it feels like to have their hands, what they were like as a child. This helps you go into unexpected places.

Swati: There’s a value in figuring out a structure for your writing life too. You can find online zoom writing communities. The Writer’s Hour is a global writing session. Find a writing buddy. Take online classes. An MFA is not necessary to write a novel. Sometimes the time and investment may make it come faster, but maybe not. Meeting other writers can help you find your first readers. Otter.ai is a transcription service that records your voice. Sometimes I narrate things because I can’t get to a computer and type it fast enough. If you have a full life, finding ways to re-engage with a long-term project really can help.

Joy: I’ll lay a notebook on my laptop or a note to myself so the next time I sit down I have to pay attention to that first. I run the Pioneer Valley Writers Workshop. It’s free to all on the first Friday of the month. Come join us and write with us.

Any final words?

Emma: Keep the momentum going by staying connected to the joy and the surprises of the process. Access that energy rather than feeling like you have to focus on control. Also keep pitching your book to yourself—coming back to what is it and why you want to write about it.

Joy: Amy Bender said, “Go where the energy is in whatever you’re working on.” Find what makes you excited to do it. Also find what takes off the pressure. If it feels too large, too formidable, how can you lessen it? Like Emma’s fragments, finding the way in through whatever crack you can gets easier the more you look for those opportunities.